Coming up with a new idea for a book is always exciting. My latest adventure in fiction, though, is quite different to anything I’ve done before. You see, although I write fiction, I also work for a teachers’ development centre for English teachers. While most of my time is spent working with teachers rather than students, and most of my writing is classroom resources about texts by other writers, I recently decided to have a serious, full-throttle go at writing fiction for students. I’ve written a few short stories for a YA audience in the past, one or two of which have found their way into anthologies but this time it’s a much more serious enterprise – writing a whole collection.

Where did the idea come from? I’ve been working recently on publications in a series called Cultural Conversations, the idea being to show students how texts talk to each other over time; how they’re part of long traditions, rather than standing in isolation. The resources bring together texts that are considered to be iconic and culturally significant with others that have been inspired by them, drawing on their themes, characters, narratives, archetypes and conventions. So, as an example, Homer’s Odyssey is brought together with the many contemporary re-envisionings by writers like Derek Walcott, Simon Armitage, Margaret Atwood or Madeleine Miller. And Amanda Gorman’s poem for the inauguration of Joe Biden is read alongside Maya Angelou’s ‘Still I Rise’ that inspired her work, and in relation to the other iconic American texts that she paid homage to.

The most recent publication in the series, yet to be published, is on Antigone. Supported by a grant from the Classical Association, we commissioned four writers to produce new work based on Sophocles’ play. Poets Valerie Bloom and Inua Ellams, fiction writer Phoebe Roy and playwright Sarah Hehir have all written texts for 11-14 year olds inspired by the Greek play. While liaising with the writers and discussing their work, I thought I’d try my hand at a short story myself and ended up writing ‘Being Antigone’, a story about a contemporary school girl whose own life has some echoes of the original. I then wondered whether I might try doing some other ‘versions’, talking back to the famous texts that school students often find themselves studying.

I was instantly captured by the idea, in part because it tied in closely with something that’s been preoccupying me for quite some time . When Michael Gove was Secretary of State for Education, his mission was to radically alter the curriculum, especially at GCSE. Gone were American authors such as Arthur Miller or John Steinbeck. All students were required to study a pre-twentieth century novel. Some kinds of writing were proscribed, others were side lined, and in the supposed cause of ‘driving up standards’, ‘challenge’ and giving students ‘cultural capital’, lots of texts that enthused students and gave them a love of literature were ruthlessly excised. Ensuring a rich mix of diverse writers of different cultures and genders was not high up the minister’s agenda.

So, students are currently reading a diet of mainly canonical texts, which are not always suitable, not always accessible, often seriously hard work rather than pleasurable for all students in that age group. The majority of the texts are by dead white men.

My ‘versions’ idea suddenly sprang to life. What if I could write lots of different angles, re-tellings and interpretations of these texts , to open up new ideas and ways of reading them? My stories could act as fresh ways in; they could offer the viewpoint of a character left on the side lines, be prequels or sequels, pastiches or serious imitations, updated versions or adaptations. Equally, they could offer many different perspectives – for instance female views and voices alongside male ones, with characters and settings that are sometimes marginalised in those canonical texts, at least some of which reflect the realities of students’ lives.

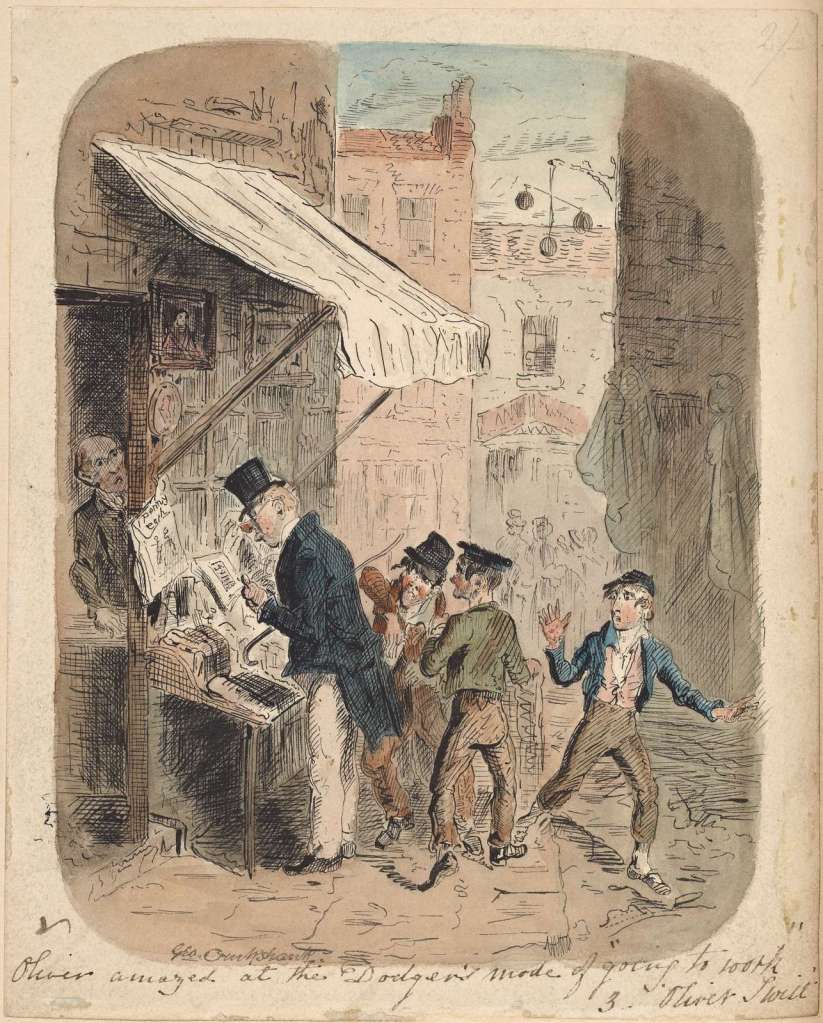

I got started on the first stories soon before Christmas, sending them to colleagues for comment before committing to the whole project. Each time a story came back with a thumbs up, I was energised to have a shot at another, moving from Jekyll and Hyde and A Christmas Carol to The Tempest, from a Shakespeare sonnet to a poem by Thomas Hardy, from An Inspector Calls to Oliver Twist. It’s been a lot of fun writing them and the scope for writing in different genres – ones I’d never tried before – has been exhilarating, taking me out of my fiction-writing comfort zone. An Inspector Calls has become An Inspector Called, where a class, reading and studying Priestley’s play, suddenly find themselves, like the characters in the play, experiencing a spookily disturbing moral wake-up call. Oliver Twist is seen through the eyes of the Artful Dodger and for Macbeth, the story of the teenage Fleance, who only speaks a few words in Shakespeare’s play, is filled out. I thought that young people might be interested in the kind of dangerous world that a boy of their own age would have had to navigate to stay alive.

The Artful Dodger and Oliver

I have looked for angles that might be enjoyable for a young adult audience but not all the stories have a teenage perspective or protagonist. Hardy’s ‘Neutral Tones’, for instance, imagines the loss of love at the end of an adult relationship, the Nurse in Romeo and Juliet is given a narrative of her own, and one story is told by an ex-teacher, now a writer. In each case, I’ve been juggling lots of different elements – how to use the source text itself and do justice to it, the teenage audience (alongside the teacher audience who will read it in the first instance and then share it with their students) and my own aesthetic judgements about what might make a good story and how I want to write it. Not easy holding all these things in mind, all at once, but it’s been immensely enjoyable to have a go at it.

The idea of intertextuality is at the heart of all literary creative endeavour. It’s also at the heart of all literary study – we appreciate Shakespeare for what he’s done with source material, for how he uses and adapts existing genres, for how his representations of race or gender compare with that of his contemporaries, for how his work has been interpreted, re-fashioned, drawn on for inspiration across the centuries. Likewise, all writers are constantly re-inventing traditions of writing, ‘putting new wine into old bottles’, as Angela Carter described it. In this project, I’ve been putting some new wine – hopefully rich-bodied and tasty rather than unpalatable and vinegary – into a crate of bottles by a range of different writers and, along the way, offering new young readers an inviting way of tasting some old vintages.

Barbara Bleiman

26th April 2022