I’ve changed my life because of a picnic I once read about in a book so it’s fair to say that I take literary picnics seriously.

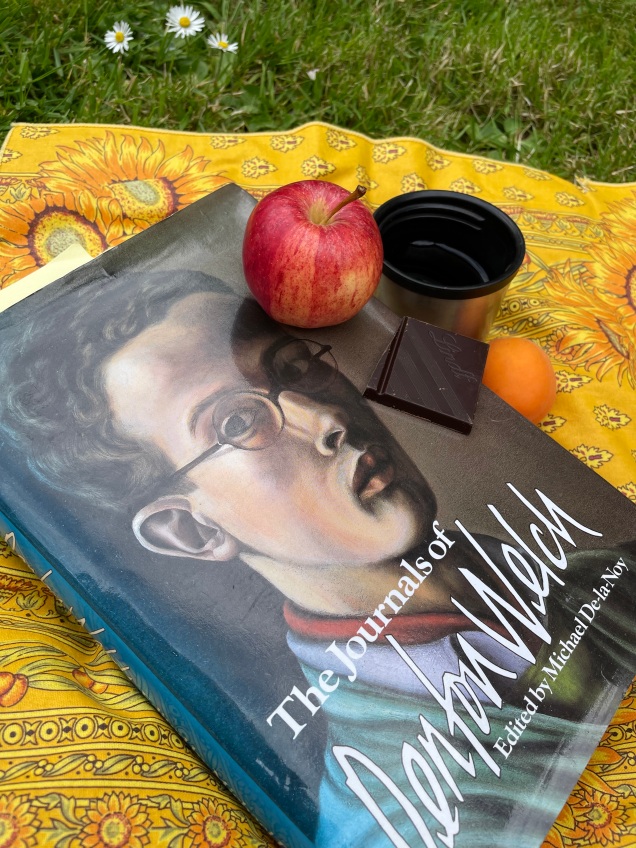

I first fell in love with the 1930s writer, Denton Welch, because of his exact accounts of picnics taken in the countryside around Kent. In our twenties and living in London, my husband and I would copy Denton’s picnics and cycle round the countryside, trying to stop in exactly the same spots Denton had.

So, several decades later, when we wanted to move back South from Edinburgh, we remembered those country lanes and moved to live in Kent, largely because of how we’d grown to love it through Denton’s picnics.

Here’s his diary entry for 26th October 1944: There were cows in the field opposite, in the misty atmosphere, and beyond on the opposite hill Tudorized houses lost in the soft mist. We ate cheese, fruit cake, biscuits, toast, drank coffee and I ate the only orange in pigs.

Then we smoked the Dunhill cigarettes that I had bought, and an old lady came behind us and said over the fence, ‘Excuse me, but would you like any boiling water? Can I get you any boiling water?’ I told her we had just drunk our thermos of coffee and she went away immediately to her house saying, “I see, quite, quite.’

Perhaps because he insisted on having picnics through the year, his best were ones that involved a thermos and four squares of dark chocolate. Four squares exactly, not a bar, or even ‘some chocolate’.

Be exact, writers, because your readers will be eating along with you.

Or nearly always. I tried to find the earliest account of a literary picnic and came up with Anthony Trollope in Can You Forgive Her (1864):

‘There are servants to wait, there is champagne, there is dancing, and instead of a ruined priory, an old upturned boat to be converted into a dining room.’

Hmmm.

But if the Trollope account is a little too aspirational for most of us, then what exactly is a picnic? Maybe it’s a breakfast of bananas and sweet corn cooked on a static barbecue in a full car park? Our annual summer holiday treat has now gone into family myth, not least because of the sight of our normally office-bound father struggling to feel at home in the great outdoors. And what could be more British than seeing picnickers sitting right next to their cars as they watch the traffic go by?

At least Patricia Highsmith took her characters off the motorway in The Price of Salt (which became the film, Carol):

Then they drove into a little road off the highway and stopped, and opened the box of sandwiches Richard’s mother had put up. There was also a dill pickle, a mozzarella cheese, and a couple of hard boiled eggs. Therese had forgotten to ask for an opener, so she couldn’t open the beer, but there was coffee in the thermos. She put the beer can on the floor in the back of the car.

‘Caviar. How very, very nice of them,’ Carol said, looking inside a sandwich. ‘Do you like caviar?’

At the other extreme, there was the time I went to play with a new school friend, and her mother threw jam sandwiches out of the window at us so we wouldn’t disturb her at lunchtime. That didn’t feel like much of a picnic so, while there should be an illusion of ‘roughing it’, perhaps there also needs some care involved.

‘You English,’ my Dutch neighbour says about the way her British husband fusses with filling the thermos, preparing fruit and yes, why not, a rug to sit on. ‘Why can’t you take some bread with you and be done with it?’

Perhaps our classic children’s literature is to blame. The lashings of ginger pop enjoyed by the Famous Five, or Ratty’s famous “cold-tongue-cold-ham-cold-beef-pickled-onions-salad-french-bread-cress-and-widge-spotted-meat-ginger-beer-lemonade — ” from the Wind in the Willows.

If Ratty had just said he’d got a picnic, even a large one, then who would have been interested? Not me. And I certainly wouldn’t have begged Mum to take pickled onions with us next time we went on a picnic.

I know I’m not alone in loving detailed food descriptions laid out on the page. Recently I had a brain freeze and couldn’t remember the name of a favourite children’s book, so I asked on social media, ‘What’s the name of the book where they have those little sugar biscuits with iced flowers?’

The Little White Horse, several people answered in minutes. And there then followed an animated discussion of all the food Marmaduke Scarlet cooked for Maria Merryweather. So perhaps it’s not surprising that Harry Potter eats well at times too, given that J K Rowling has admitted how Elizabeth Goudge has influenced her.

Among the classics, Jane Austen is the mistress of the niceties and challenges of a picnic – perhaps because she gets so well how it could all go horribly wrong. Her deliciously snobbish Mrs Elton in Emma, has all the important details planned in advance, as she explains to Mr Knightley. ‘I shall wear a large bonnet and bring one of my little baskets hanging on my arm…. Nothing can be more simple you see… There is to be no form or parade – a sort of gipsy party. We are to walk about your gardens, and gather the strawberries ourselves, and sit under trees; and whatever else you may like to provide, it is to be all out of doors, a table spread in the shade, you know. Everything as natural and simple as possible.’

But Mr Knightley is a man I could never fall in love with. He insisted on having the meal inside with servants and furniture, large bonnets optional.

Perhaps he was feeling under siege like the poor oysters flattered into joining the walrus and the carpenter on their sea-side picnic until:

‘A loaf of bread,’ the Walrus said,

‘Is what we chiefly need:

Pepper and vinegar besides

are very good indeed –

Now if you’re ready, Oysters dear,

We can begin to feed.

I used to love this poem until I’d realised exactly what was going on. Perhaps the best literary picnics – like many in real life – are those that teeter on the verge of disaster, such as the glorious beach picnic in Gerald Durrell’s short story ‘The Picnic’, where the family settled on what they thought was a rock but turned out to be the side of a dead horse.

I wonder too if the weather is another reason why the British love eating outside? Because we can never really plan ahead for a sunny day, we don’t let a ‘spot of weather’ put us off. As Edwin Morgan writes:

In a little rainy mist of white and grey

we sat under an old tree,

drank tea toasts to the powdery mountain,

undrunk got merry, played catch

with the empty flask…

In her wartime diaries, Love is Blue, Joan Wyndham writes about one definitely un-Blyton picnic: ‘We lay under a tree in the wind and the rain eating peaches while Zoltan kissed my thighs with his usual air of grave, sad absorption. He undid his shirt so I could put my hand over his heart, and the wind roared in the trees and whipped back my hair.’

Can’t you just taste those peaches?

Oh, your attention went elsewhere? Back to the food, people.

Although not perhaps PG Wodehouse’s picnic in Very Good Jeeves:

I met a fellow the other day who told me he unpacked his basket and found the champagne had burst and together with the salad dressing had soaked into the ham, which in turn had got mixed up with the gorgonzola cheese forming a kind of pasta … Oh, he ate the mixture but he said he could taste it even now.

Well, if the food isn’t that good, at least a picnic can offer the chance to explore. Not just a geographical place, but to escape the routine of day-to-day. A packed lunch made at home to take to the office every day is NOT a picnic. However, the same food brought by someone coming to surprise you with a lunch to take outside in the park is definitely a picnic in my book.

So a picnic can help us try something new. Escaping the routine of day-to-day. Which is, after all, very much what reading for pleasure can be.

‘O stop, stop,’ cried the Mole in ecstasies: ‘This is too much.’

‘Do you really think so?’ inquired the Rat seriously. ‘It’s only what I always take on these little excursions, and the other animals are always telling me that I’m a mean beast and cut it very fine!’

The Mole never heard a word he was saying. Absorbed in the new life he was entering upon, intoxicated with the sparkle, the ripple, the scents and the sounds and the sunlight, he trailed a paw in the water and dreamed long waking dreams.’

Sarah Salway, May 2023